On November 1st, Epidiolex became the first FDA approved drug derived from natural cannabinoids to hit pharmacy shelves in all 50 states. News outlets everywhere are touting Epidiolex as a breakthrough product that will create an avalanche effect for the future of cannabis and medicine.

But for people privy to the wonders of cannabis, this information is not new. Since Sanjay Gupta’s 2013 documentary, Weed, CBD has been widely known by the general public to help seizure symptoms for children and adults alike. So, why now? Why is it this particular medicine that gets FDA approval? And what does it mean for the future of cannabis?

What’s Epidiolex?

Created by GW Pharmaceuticals, Epidiolex will save lives and improve the quality of life for patients who suffer from daily seizures. The drug treats two different types of childhood-onset epilepsy: Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsy and its symptoms have been scientifically proven to improve with cannabis, including two prominent studies on the matter. In one report conducted by the company, Dravet syndrome patients who took Epidiolex were three times more likely to experience a significant reduction in seizure frequency.

After initial FDA approval of the drug, the DEA reclassified Epidiolex to a schedule V substance, the least restrictive classification. Cannabis advocates have been pushing for reclassification of the plant (or at least CBD) for years because it means fewer restrictions on medical research and more lenient sentencing in states where cannabis remains illegal. It was only after the FDA approval of Epidiolex that the DEA changed its stance on cannabis for the first time in 46 years, to lighten the schedule for CBD. However, there’s a catch; instead of choosing to reschedule CBD in general, the DEA announced they would only reclassify CBD in products “approved by the FDA.”

However, there’s a catch; instead of choosing to reschedule CBD in general, the DEA announced they would only reclassify CBD in products “approved by the FDA.”

Those four extra words call attention to who exactly is allowed to determine what is and what isn’t medicine. When asked about the launch of Epidiolex, CEO Justin Gover said, “knowing the difference between real, federally-approved medicine and alternative treatments is key when it comes to cannabis.” While everyone can agree that there’s a way to use cannabis to your medicinal benefit and there’s another way to utilize cannabis for fun, Gover’s statement is concerning.

We’ve all experienced or know someone who has experienced a change in opinion regarding cannabis overtime. But when the most prominent opponents of cannabis (Big Pharma, the FDA, and the DEA) turn a new leaf, we should be skeptical of their motivations. Are we really supposed to place confidence in those that considered cannabis to have no medicinal value for long after it was proven otherwise?

The FDA: an institution for the people?

By approving Epidiolex, the FDA became the official gatekeeper for what CBD medicines are legal. According to the CEO of GW Pharmaceuticals, “where there are products that don’t meet FDA standards and have not been approved by [the] FDA, we don’t believe that they should be appropriately termed as medications.”

In theory, he is right. The FDA should provide a level of consumer protection that is needed in the cannabis industry. However, many cannabis consumers are concerned about the launch of Epidiolex and what it means for the medicine they rely on. Parents of epileptic children are worried that the release of this CBD product will threaten the availability of CBD products they have trusted for years.

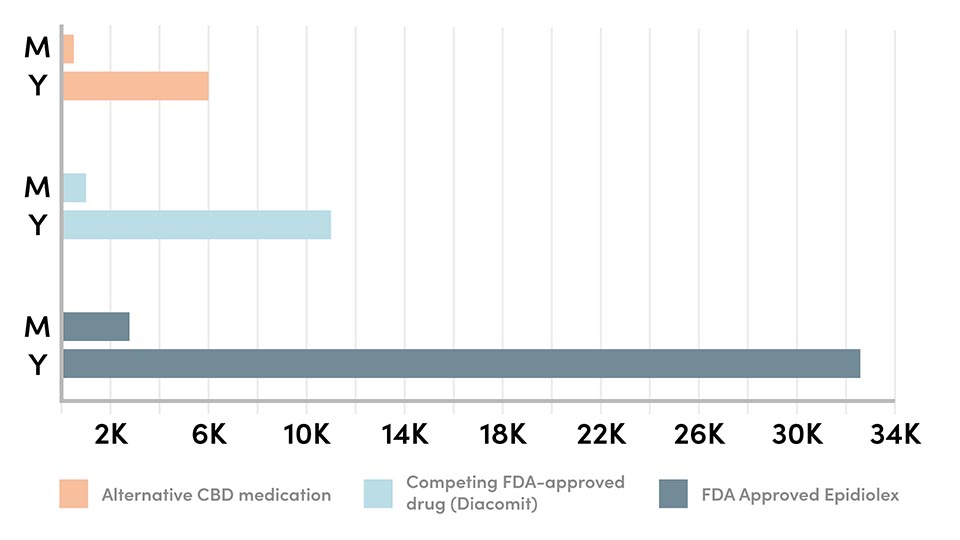

Their concern is founded: in multiple states, GW Pharmaceutical has lobbied for language in laws surrounding CBD to specifically say FDA-approved products are the only medicine a parent can legally purchase to treat their child. Of course, that would not be such a big deal if the FDA-approved drug was affordable. It’s not; Epidiolex will cost the average patient $32,500 a year. While GW Pharmaceutical representatives say this is consistent with competing FDA-approved epilepsy drugs on the market, it is a drastic jump from what cannabis users are currently paying for CBD products at dispensaries.

Cannabis consumers may be wary for another reason. Like many government institutions these days, the FDA has lost the public’s trust in recent years. It’s no secret that their approval of heavy-duty opioids helped pave the way for the current opioid crisis in the country today. Despite the outcry around opioids, the FDA approved an opioid tablet 10 times stronger than fentanyl last week.

In cannabis, there is certainly a need for us to be able to discern a good product from a bad one; perhaps the FDA could help in doing so. In the past, cannabis marketers have relied on a lack of regulation to imply their product can do things that may not be true. But with cannabis still illegal federally, we are without much-needed research to prove all the health claims about cannabis going around today. As long as cannabis remains a schedule 1 drug, it is very difficult to research it to the extent the FDA needs to consider it legitimate. As long as cannabis is illegal federally, the few institutions who can afford to do the research necessary are mostly large pharmaceutical companies.

In a recent study conducted by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, the drug development process to earn FDA approval costs the average company $2.6 billion dollars. To acquire approval for a new drug, manufacturers must “conduct lab, animal, and human clinical testing and submit their data to FDA.” According to Jamie Roitman, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, “getting approval for any study involving people and compounds related to marijuana is ‘very difficult.’” Roitman herself is limited to conducting her studies on rats.

Once it is approved, add up to $312 million for post-approval research and development that consists of “studies to test new indications, new formulations, new dosage strength and regimens, and to monitor safety and long-term side effects in patients.” This step is required by the FDA as a condition of approval. Even if a company is willing to foot that bill, they are taking a major financial risk: there is only a 12% approval rate for drugs that are submitted for FDA approval.

The companies behind the curtain

Before Epidiolex, the FDA had only approved cannabis-related drugs in the form of synthetics. In November 2017, the FDA approved “Dronabinol,” a drug developed by Insys Therapeutics that incorporates synthetic delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) to treat nausea and vomiting for cancer patients. The name Insys Therapeutics may sound familiar: they played a major role in the ever-expanding opioid epidemic. Last year, U.S. prosecutors pointed to the company’s founder as a co-conspirator in a case involving “six former executives and managers of participating in a scheme that involved bribing doctors to prescribe a fentanyl-based drug, according to a court document,” Reuters reports.

Not only are the companies who own the only “legitimate” cannabis-related medicines linked to the opioid crisis; they are the same companies that poured thousands of dollars into lobbying campaigns aimed at hindering the process of legalization. Insys Therapeutics contributed $500,000 dollars to combat a cannabis legalization measure on Arizona’s ballot in 2016. GW Pharmaceuticals and their U.S. subsidiary, Greenwich Biosciences, became heavily involved in the elections of several states (such as South Dakota) that considered exempting CBD from the definition of cannabis so that it could be rescheduled to a less restrictive classification.

Instead, GW Pharmaceuticals lobbied to reschedule only CBD products that were approved by the FDA.

Instead, GW Pharmaceuticals lobbied to reschedule only CBD products that were approved by the FDA. The motivation behind this move is clear: cannabis legalization will lead to more competitors in the “legitimate medicine” industry, which will affect the stock of companies like GW Pharmaceutical. Guaranteeing that the only legal medicine must be FDA-approved is a great way to squash any future competition, making it challenging (if not impossible) for smaller companies to compete.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em

Why are the companies that fought against cannabis for so long the same companies that are now profiting off the plant? The answer is unsurprising: money. As long as cannabis remains a schedule 1 drug, pharmaceutical companies are among the few that can utilize loopholes and gather the funding necessary to do the very research needed to get FDA approval. This is why Epidiolex may not signal a win for cannabis legalization; the company behind the drug has little motivation to fight for cannabis legalization on the whole, and more motivation to keep it illegal, with the exception of their product.

Over the years, cannabis has posed a huge threat to Big Pharma and their opioid sales in particular. A recent study reported that nearly half of those who use cannabidiol products stop taking traditional medicine. Because legalized cannabis is proven to lead to less opioid consumption in chronic pain patients, the makers of the multi-billion dollar industry were not eager for this change. Now that legalization is inevitable and popular opinion has shifted, the same companies that are responsible for the lag in legalization are cashing in.

What this means for cannabis

Although the approval of Epidiolex is considered a medical breakthrough, its launch brings to light an ongoing pattern: an unfair distribution of wealth generated by the new legal medicine market that may not bode well for consumers. The reality is that the products being deemed legitimate by the FDA are not coming from cannabis advocates, but large corporations that have realized working with cannabis is more profitable than continuing to fight against it. While we are making progress in lessening the severe equality gap created by the War on Drugs, we must be careful not to let legalization and the “legitimization” of cannabis become a reorganized version of the same structure that has failed us before.