Cannabis has survived through long periods of criminalization and stigma through spaces and events like music festivals. But as legalization slowly spreads and music festivals get bigger and more corporate, how are festivals reconciling laws, sponsors and attendees?

American music festival culture is a behemoth spanning decades, responsible for great cultural shifts that put us where we are today. The first American music festivals can be traced to the Newport Jazz Festivals in the mid-to-late 50’s showcasing the likes of Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong and Chuck Berry. But the music festivals as we recognize them today owe the most to the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival and Monterey Pop, one week apart from each other in the summer of ‘67, two full years before the first Woodstock, well-known for featuring The Doors, The Byrds, Janis Joplin and the first major American appearances for The Who, The Jimi Hendrix Experience and Otis Redding.

This might seem familiar to the way that the festival circuit nowadays seems to dictate our collective taste in popular music (or be dictated by, depending on how you view the chicken/egg question of the commercial music industry’s influence over us), but the influence of festivals stretches beyond our hit lists and streaming numbers. The aforementioned festivals are considered to have been the catalyst for the “Summer of Love”, a cultural movement beginning in the late ‘60s that still reverberates in our politics and culture today.

Music festivals and its sub-genres, including cannabis festivals, have long existed as “temporary autonomous zones”, a socio-political form of protest that creates spaces to elude formal structures of control, eg. social norms, laws and law enforcement. For example, you might consider LGBTQ+ bars and clubs over the decades as an example of such tactics. These spaces allowed marginalized people to simply be, when at best they were stigmatized, harassed and assaulted by the public at large and worst when they were criminalized for existing.

Similarly, festival spaces have been a long-standing example of these autonomous zones. Decades-old cannabis festivals like Hempfest in Seattle or Hash Bash in Ann Arbor have celebrated cannabis publicly and en-masse at odds against, but undisturbed by law enforcement. You might remember the latter as a celebration of John Sinclair’s release in 1971, who was targeted and arrested by an undercover police sting for selling two joints. John Lennon wrote a song about the situation and even headlined a “Free John Now” benefit in his name, eventually leading to the Michigan Supreme Court ruling their cannabis laws unconstitutional.

It’s hard to overstate the impact that these spaces and moments of history have had on our collective psyche. Positive public opinion towards cannabis legalization has continued to rise over the years, due in part to positive portrayals in the media today, but which was built on the foundation of positive sentiment maintained underground for decades.

Even today, Coachella and many other modern festivals like it still officially forbid the presence of cannabis and related paraphernalia (even if they take place in states where cannabis is legal, shout out to Phillip Anschutz), but any attendee can tell you that once you’re past the security checks, the festival grounds are decidedly… unreflective of official policy.

But interestingly enough however, as legal cannabis has spread and matured, it’s found its way back into mainstream music festivals as corporate sponsors themselves, and even producing their own events. Albeit, often in strange half-measure ways necessary for dodging both federal regulations and occasionally the venue policies of the parks they take place in. This puts cannabis in a weird legal limbo exemplified by the hard enforcement immediately surrounding festival spaces juxtaposed against the free-for-all wonderland at its heart.

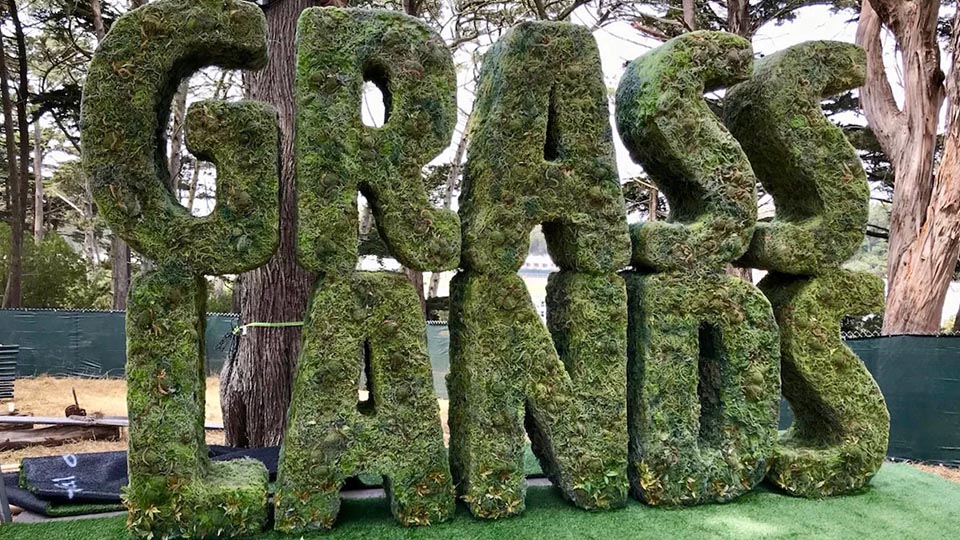

For example, last year’s Outside Lands in San Francisco, CA debuted “Grass Lands” alongside their ongoing Beer and Wine Lands that celebrate the respective local Californian industries. But there was no actual consumption allowed, consistent with the policies of Golden Gate Park where the festival is held. Alcohol is readily sold and consumed, but visitors to Grass Lands were merely allowed to speak to brand ambassadors or partake in un-infused treats. While the experience may have been anticlimactic, Superfly (the company responsible for Outside Lands, as well as Bonnaroo in Manchester, TN) has noted that this was a trial run, so we can hope future iterations will feature a more hands-on experience. Similarly, getting to Bonnaroo in Manchester can be notoriously risky. As one of the biggest, most free-wheeling festivals, it also happens to exist at the geographical center of hardline Tennessee drug policy.

Grass Lands by Acme Scenery – CC BY

Similarly, Life is Beautiful, which runs every year in historic downtown Las Vegas (by Fremont, not the Strip) features free shuttles that ferry attendees to dispensaries and back while still officially forbidding cannabis consumption within the festival. Even Rolling Loud, one of the largest hip-hop festivals in the country (takes place in both Miami and Los Angeles), also officially decrys the onsite use of cannabis despite the literal denotation of the festival name.

On the other end of the spectrum, cannabis festivals that are expressly cannabis-focused have grown into massive affairs with international appeal, where cannabis cultivators, brands and distributors vie for prestigious accolades like Best Edible and Best Strain and where enthusiasts can sample the best and newest the industry has to offer. Festivals like Mike Tyson’s Kind Music Festival are some of the first to truly integrate cannabis and music which can hopefully set the precedent for similar events to come.

These oxymoronic policies are a microcosm of a larger struggle for the soul of both cannabis and modern music festivals. While you can still find secret, niche festivals with no corporate sponsors that resemble the “protestivals” of old, the growth of the entertainment industry, rising income inequality and social media have all contributed to a booming mainstream musical festival industry fueled by corporate and advertising dollars. As cannabis remains illegal on a federal level, many of these sponsors are reticent to fully welcome the plant.

Ultimately, while the progress cannabis has made in recent years has been monumental, the gears of government and bureaucratic move slowly and the decades of anti-cannabis propaganda wear even slower. In contrast, at a time the pinnacle of American counterculture, music festivals have become a hot, lucrative commodity that thrives in the age of social media and an ever growing entertainment industry. While the two are historically and inexorably intertwined, there are bound to be growing pains as one outpaces the other. Legalization did not solve all our problems overnight.